Rural Charge Weekly #9: Rewiring Rural Mobility for an Aging World

The urgent need to future-proof transport in rural areas to support aging communities and a shrinking workforce.

In last week’s post I began a conversation about how to tackle the challenges that aging rural communities pose to transport policy makers and service providers. I see this as perhaps the most conversation we should have because their future will increasingly be driven by older people, many retired who comprise the majority that live there.

This week, I want to delve a little deeper, and to imagine how we can rewire our rural transport systems. This is emerging as one of the great design challenges of the 21st century that provides an opportunity for the scientific and technology communities to collaborate with local people to create age appropriate solutions that enable more people to live independently for longer.

The process of aging is deeply personal. Some people take it in their stride, others resist it with vigour. The reality that one day (and that day will arrive), where we no longer have our independence, the point when we need support from others, is an uncomfortable one to think about.

However. think about it we must as mobility equals autonomy: Take away the car keys without providing alternatives, and you take away a piece of dignity and freedom.

Before we look at the role that innovation can play, let’s remind ourselves why mobility matters so much in aging societies, and what risks loom if we fail to adapt.

Demographic Shifts and Challenges

All over the world, people are living longer and having fewer children. By 2030, 1 in 6 people on Earth will be aged 60 or over, and by 2050 that population will double from 12% to 22% to reach 2.1 billion people.

Many countries will have unprecedented “grey majorities,” with seniors over the age of 65 forming a huge share of society. For example, Japan’s population is already nearly 30% over 60 and by 2050 a full one-third will be 65+.

European nations aren’t far behind – Italy is the oldest country in the EU (about 24% over 65) and Germany and France’s senior populations are rapidly growing.

Even developing countries are aging fast; China now has the world’s largest number of elderly citizens, and its 65+ group is set to reach roughly 30% of the population by 2060.

These demographics pose serious social and economic challenges. With fewer working-age people supporting more retirees, the strain on pensions, healthcare, and labour markets is immense.

A shrinking workforce means fewer bus drivers, taxi drivers, and caregivers just as demand for such services among older people skyrockets. Our policymakers worry about dependency ratios, but there’s a more immediate, human scale crisis unfolding in daily life – mobility. How will millions of older adults, many in rural or suburban areas, get where they need to go when they can no longer drive safely or walk to a bus stop?

Mobility Is Independence: Why Transport Matters as we Age?

We’ll all reach a point in our life where one or more of these things happen to us:

We lose a partner (husband or wife) because of death or divorce

We develop a mental illness (e.g. Dementia)

We are diagnosed with a cancer.

We become less physically mobile as our limbs and joints start to creak.

Sorry to be so depressing but these are the facts. Better we tackle them head on don’t you think?

When (rather than if) our health starts to fail and we don’t have a partner around to drive us to the doctors, dentists or visit friends and relatives, having easy access to transport can determine whether we can “age in place” at home or need to move into a care home. Indeed, ease of access is considered a key social determinant of health for older adults. When we lose the ability to travel freely, our world shrinks – sometimes literally shortening our life.

A Universal Issue but Experienced More Acutely in Rural Communities

Numerically, in the UK and other Western European and North American countries, the majority of people aged 65+ live in and around cities and towns where buses, trains, or taxis are more readily available to help them get around once they stop driving.

However, as is well documented, in rural communities, those options are often sparse or non-existent. The car remains king.

In the UK, for instance, 18% of people aged 65+ in rural areas say they never use public transport because it simply isn’t available (compared to just 2% in urban areas). Little wonder then that 68% of UK households with someone over 70 keep a private car – driving themselves is often the only option.

Fear of the day that they can no longer drive safely is understandable. Research by Nissan UK who have been a key partner in the development and trial of autonomous cars on UK roads revealed that over half of drivers over age 70 said that they would feel disempowered if they had to give up driving, and nearly two-thirds stress the importance of not having to rely on others for basic trips.

Declining ridership and budget cuts mean many rural bus routes have reduced services or vanished entirely, and let’s be under no illusion, in their current form, they won’t return in any meaningful way in spite of statements from the Government to “level up” places outside of London.

The problem feeds on itself: as populations age and dwindle, there are fewer fare-paying passengers making rural public transport financially unsustainable.

Japan has come to the point of raising the mandatory retirement age for taxi drivers to 80 years old to keep enough drivers on the road in rural areas facing “an acute shortage of transportation for the elderly.”

Other countries including the UK face similar conundrums: who will drive the community minibus or operate the ambulance when the pool of younger workers and volunteers is drying up?

Rural areas are confronting a perfect storm – more seniors needing rides, but fewer humans available to provide them.

The Cost of Inaction: Isolation and Economic Strains

What happens if we ignore this growing gap in mobility? The short-term signs are already apparent. Many older adults simply stay at home when no transport is available – missing medical appointments, skipping social activities, and becoming increasingly isolated.

Health & Wellbeing: In practical terms, an elderly person who can’t drive and has limited access to a bus might not get a flu or COVID shot or might delay care until a small health issue becomes a crisis. The human toll is immeasurable, but even economically, it translates to higher healthcare costs and burdens on social services down the line.

Road Safety Risks: There’s also a safety risk in the short term. In car-dependent rural areas, older people continue driving longer than they should, simply for lack of alternatives. This can lead to increased accidents (for themselves and others) as vision, reflexes, or cognition decline.

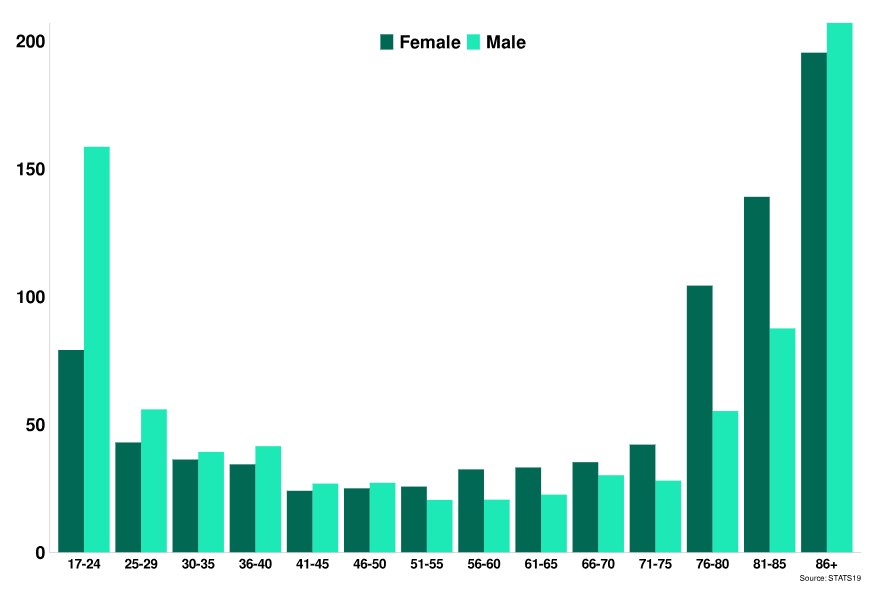

Reporting from the UK’s Department for Transport confirms that age plays a prominent role in determining the number of fatalities and serious accidents.

Young drivers and those over 75 are most likely to be involved in an accident.

Driver Casualties Per 1 Billion Miles Driven bu Age and Gender

Source: Department for Transport

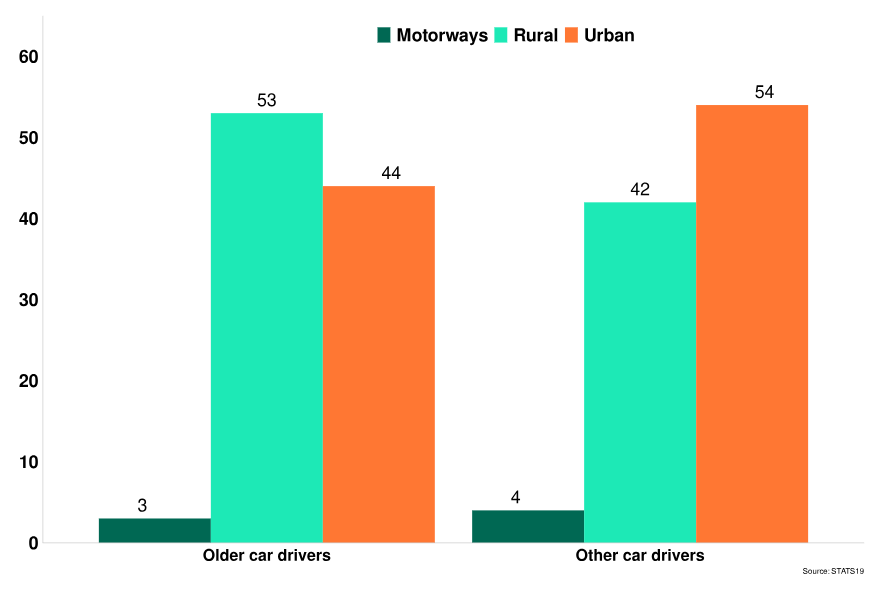

What’s more, the older the driver is, the more likely it is that these accidents will take place on a rural road.

Accidents by Road Type and Age

Source: Department for Transport

Why do more of these accidents take place on rural roads? Anyone who has spent time driving on them, especially when it’s dark appreciate that there are many hazards that demand complete concentration. Something as simple as a car coming towards you without its headlights dimmed increases the chances of an accident. More so when the person is older and has failing eyesight or is easily distracted.

Economic & Social Decline: Without action, we could see a future where whole villages essentially “shut in” their elderly residents. Rural economies suffer when they are dependent on a large constituency of older people who can’t easily leave home to shop or participate in community life – fewer customers for businesses, fewer volunteers for community events, and a loss of the wisdom and experience seniors offer

Rural Depopulation: When faced with the choice of spending the last few years of their life in a village with dwindling social and healtcare services or moving nearer to a city that is better resourced, many older people may choose the latter. If this materialises, it not only accelerates rural depopulation but places more pressure on straining city healthcare and transport systems.

No Cost Free Options: Inaction on mobility is not a cost-free option – it will either extract a toll on the health and wellbeing of our elders or cost societies in the emergency measures that need to be taken to cope with the cost of supporting more people with mobility needs. We can pay for a solution now or pay a much higher price for the fallout later.

Designing for Dignity: Technology, Policy, and Human-Centred Innovation

How do we avert this crisis? Part of the answer lies in reimagining vehicles and infrastructure through the twin lenses of technology and empathy. This is not just about adding more features to mobility products/services but about fundamentally asking: What do older people living in rural communities need from transportation to live full, healthy lives, and how can we provide it?

Human Centred Tech Design: Not a “Cut and Paste” Job

Globally, new mobility technologies that address the need to decarbonise transport and remove the dependency on a depleted pool of human drivers attracted $54 billion dollars in investments in 2024. Business cases are based on the premise that revenue growth will happen most rapidly in cities and towns where most people live. Scaling a business is above all else a numbers game.

However, designing for the masses who live in the centre creates a risk that the needs of those who live on the edges are overlooked. Not intentionally but simply because they are what an investor might call “edge cases”.

Living on the edge, out in the countryside and on our islands, are many older people who will watch and read about these innovations but rarely experience them because they only occasionally, if ever need to visit the city.

Maybe, if their health holds up and they are able to live long enough, a slightly modified version of the urban mobility innovation will arrive in their village. Minor modifications because the cost of developing the product/service for a segment of the market that is small in number far outweighs the benefits.

“Cutting and pasting” an established product/service into a small market is standard operating procedure for vehicle manufacturers and transport service providers. When have you ever driven or travelled in a vehicle that was purposely designed for people living in a rural community?

Left to their own devices, tech businesses may be happy to follow this proven methodology. However, demographic changes, and the need to preserve the fabric of rural communities are forcing the hand of laissez-faire policy makers.

As the number of older rural residents increases (many of whom have relocated to the countryside for a “quite life”), their voices and votes which are generally over-represented in elections will carry even greater weight. They won’t “settle for second class”: Second class solutions to their mobility needs.

Human Centred Tech Design: Pay Attention to the Rural Baby Boomers!

The rural communities that are home to a growing number of people who have retired but still want to remain socially and politically active are places that demand special attention from policy makers and product designers.

Thanks to social media and YouTube, the Baby Boomer generation are tuned into the latest tech innovations. They have time on their hands to do their research and chat about what they discover with their children and grandchildren. They value their quality of life, are well connected, and won’t be shy about shouting about what they expect from the tech community.

Case in point: My 84 year old father spends many hours watching videos on YouTube that are hosted by technologists and futurists. When we speak, conversations often turn to the latest video he’s watched about electric, hydrogen fuel cell or autonomous vehicles be they cars, trucks or tractors. He’s a farmer not an engineer or a scientist but when he asks me questions, they are all well considered.

While they can still drive, and before autonomy removes the need to do so, they want affordable vehicles that are purposely designed for the rural roads they spend most of their time driving on. What use are large, petrol guzzling SUVs on narrow rural roads? When you are living off a pension why would you want to waste money on a high spec car?

What they really want is a smaller car that offers suitable driver aids that are easy to discover and use. No touch screen displays chocked full of menus. If it’s an electric car then you want it have a charger that makes it super easy to connect to a chargepoint. No clunky cables please. Wireless or automated charging solutions would be great. With a scarcity of car mechanics and technicians in, or anywhere close to their village (they’ve closed down), a car that withstands the worst of winter weather and doesn’t need to visit the garage/repair centre would be a bonus.

In the UK, the Motability Foundation and the Designability organisation are doing important work to drive the research and design agenda for an aging and less mobile society.

When the moment arrives and driving isn’t an option due to declining health, the possibility that a fully autonomous car could step in as a replacement will be hugely appealing, particularly to elders who for better or worse, really don’t want to be seen using community transport or asking for lifts. They may be getting old, but they still prize their status. Moreover, those with more savings and larger pensions may be happy to pay a premium to retain this status. Not all pensioners are penniless!

Their ask of autonomous vehicle designers and the supporting technology developer ecosystem are straightforward. Speak with us and spend time in the place where we live. Not just a day here and there but sufficient time to fully understand our mobility needs today and int the future, and the roads that these autonomous cars will spend most of their time on.

They need complete confidence that each time they gingerly step into the car that it will behave perfectly. No veering off to the edge of the road or randomly diverting down a farm track. Assuming they can converse with it, they absolutely need it to know that just because they are old and their mind isn’t as sharp as it used to be, it doesn’t mean that it should make all the decisions for them.

Human Centred Tech Design: Retaining the Human Touch

While advances in transport technologies continue at pace, it’s worth pausing to consider the human implications of relying on automation versus human support. On one hand, robots and autonomous vehicles don’t get tired, don’t retire, and can work 24/7. They might truly be the only way to serve ultra-rural areas in the long term.

On the other hand, there’s an emotional component to mobility. A friendly bus driver who chats and checks on an older passenger provides social interaction that a driverless shuttle cannot. Fully automating everything could inadvertently cut off one of the last human contacts some isolated seniors have in their day.

The ideal path is likely a combination: use automation to cover gaps and do the heavy lifting, but keep humans in the loop where empathy, personal care, and oversight are needed. For example, an autonomous minibus might still have a human attendant or remote operator to assist passengers, or a ride-hailing app might include a phone call from a human dispatcher to make them feel secure.

The bottom line is that we must design systems that are not only efficient, but comforting and trustworthy.

Steering Toward an Age-Friendly Mobility Future

The freedom to move – to go where we wish, when we wish – is deeply woven into the human sense of independence and dignity. Preserving that freedom for as long as possible is a priority that we should all cherish.

We need vehicles that can drive themselves, but also communities that don’t leave an elderly person standing at a bus stop on the side of a country road waiting for a bus that will never come. We need smart policies that fund the unglamorous necessities (like rural pavements, better and smarter bus shelters, and reliable broadband alongside flying cars and delivery drones.

Above all, we need a vision of mobility that values support as much as speed. The goal is not just efficient transportation, but inclusive transportation. In an era when the majority of babies born today may live to 100, designing for older adults means designing for all of us eventually. If we get it right, we not only avert a crisis, we create a world where longevity is not a burden but a blessing.

The demographic writing is on the wall, and the clock is ticking. It’s time to hit the accelerator on rethinking transport for aging societies. The road ahead belongs to everyone, no matter their age. Let’s make sure it’s one all generations can travel with confidence and dignity.